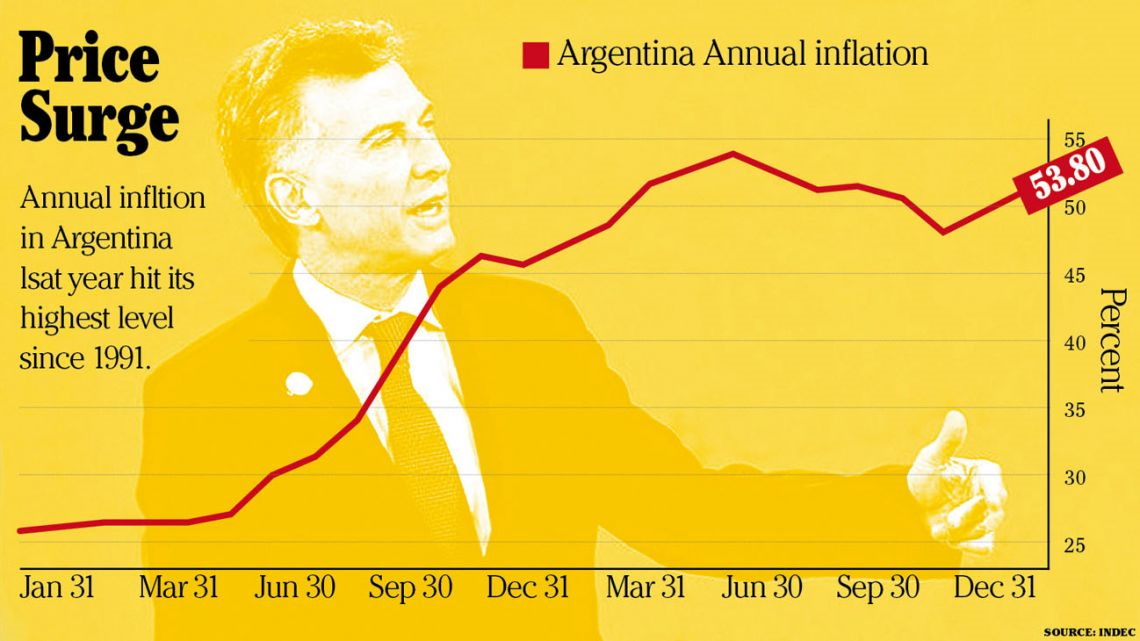

Argentina’s consumer price index accelerated in December by 3.8 percent, lifting the country’s inflation rate for 2021 to 50.9 percent – one of the highest rates in the world. The data, posted by the INDEC national statistics bureau on Thursday, underlines Argentina’s continued struggle to tackle runaway price increases. In 2020 – a year when the economy was almost paralysed due to the Covid-19 pandemic – inflation totalled 36.1 percent.

In its 2022 Budget bill, which was rejected by Congress last December, the government projected an inflation rate of 33 percent for the next year. Opposition lawmakers consider that estimate to be “unrealistic,” as do experts. According to the most recent Central Bank survey of consultancy firms, analysts and banks, prices will soar 55 percent over the next 12 months.

The largest price increases in 2021 were in hotels and restaurants (65.4 percent, up 5.9 percent in December alone), transport (57.6 percent) and food (50.3 percent). Core inflation rose in December to 4.4 percent, compared to 3.3 percent the previous month. Beef, one of Argentina’s most iconic exports, rose by 60 percent over the last 12 months. “During 2021, the government tried to anchor inflation by basically regulating the price of utility tariffs and the exchange rate,” said Hernán Fletcher, of the Centro de Economía Política Argentina (Argentine Centre of Economic Policy). “Although it certainly was not a success, without this, inflation would have been higher.”

Argentina has had strict exchange controls in place since 2019, allowing individuals to buy just US$200 dollars a month at the official rate, a move adopted in order to protect Central Bank reserves.

Argentina is in the midst of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund for an extended facilities fund agreement to replace the record US$57-billion stand-by agreement signed in 2018 with the Mauricio Macri administration. The country’s debt to the Fund totals some US$44 billion. President Alberto Fernández refused to take delivery of the remaining tranches of the loan upon taking office in December 2019.

Talks, however, are not progressing as both sides would like. The Fernández administration has been unable to agree a new deal, in large part due to a disagreement over fiscal discipline and the size of Argentina’s deficit in the coming years. “For us, the word ‘austerity’ has been banished from the discussion; for us we have to grow,” President Fernández said last week. “We have managed to reduce the primary deficit, not because of less investment but as a result of growth.”

With the country’s liquid international reserves estimated to be below US$4 billion, Argentina faces payments to the IMF of US$19 billion this year and another US$20 billion in 2023, plus US$4 billion in 2024. “An agreement with the IMF may improve the economy in terms of expectations, but in terms of inflation I don’t see 2022 being very different to 2021,” said economist Pablo Tigani.

‘We need everyone’ Reacting to the data, President Alberto Fernández said it was urgent to find a solution to the problem, as he unveiled a new round of price controls. Speaking at an event announcing an extension of the government’s ‘Precios Ciudados’ programme, Fernández confirmed that price controls would be extended for more than 1,300 products until April and argued that inflation “does not have a single cause.” “Inflation in Argentina is not the result of monetary emission but the result of many things,” ranging from “the psychological to the monetary,” he declared.

“I am pleased that everyone has understood that we need to put an end to the problem of inflation, and for that we need everyone. It is not a problem that we can solve by hitting the shops, nor is it a problem that you can solve if we don’t all come to some sort of agreement,” said the president.

Opposition lawmakers, however, rushed to criticise the government for price hikes. “Argentina is among the five countries with the highest inflation [rate] in the world. This continues to be a chronic problem in our country: since the return to democracy, we have had an average inflation rate of 48 percent (excluding hyperinflation),” said national deputy María Eugenia Vidal stressed on Twitter.

Criticising the annual rate, PRO party leader Patricia Bullrich, in turn, remarked: “A government applying recipes that have failed, on board a ship with no direction and no plan, suffocating Argentines with taxes, with millions of people falling day after day below the poverty line.”

During the Mauricio Macri administration’s final year in office, 2019, prices increased by 53.8 percent, according to INDEC data.