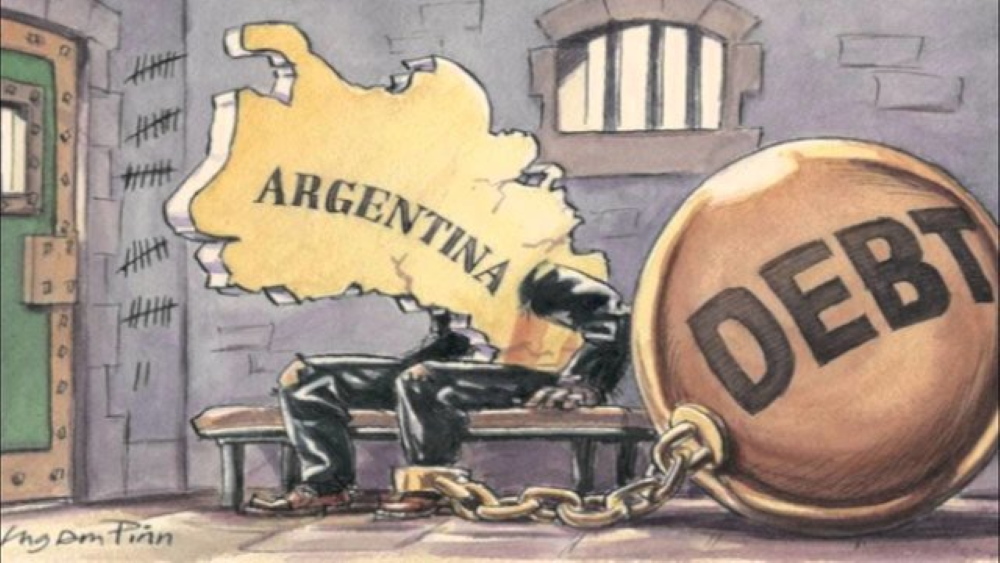

Spenders and savers in Argentina are in for a nightmare this month and next as the economy experiences a rare time of abnormality.

The primary goal of the first hundred days of Alberto Fernández’s presidency, which now seem like another century, was to revive the country by forming a socioeconomic council consisting of the conventional troika of the government, businesses, and labor unions (which, of course, never materialized). As his first 100 days in office draw to a close, President Javier Milei has called on provincial governors to sign ten points of consensus in central Córdoba on May 25, the national day, betting on a federal rather than corporate accord. This figure is in line with the ten points of the Mauricio Macri presidency from five Mays ago, but it doesn’t say much more than that. Macri’s ten points were narrow concessions made in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid an election disaster, not general free-market claims. Is there any hope for a different outcome because of these differences?

Even though Milei, a professional economist, would be pleased to see businessmen and unionists removed from the table, it doesn’t mean the governors will automatically agree on anything. If that were the case, the federal revenue-sharing reform that was mandated within two years of the 1994 constitutional reform would have been put into place long ago. There are competing regional interests on top of the unprecedented political and ideological divisions that emerged from last year’s elections (four governors have already decided not to run). If the return of income tax—from which the provinces stand to collect 70 percent—can smooth parliamentary passage of at least some fragments of the frustrated omnibus bill on the basis of a working arrangement with the governors, then we will know long before May 25 whether it is going anywhere.

While Alberto Fernández and Mauricio Macri are both irrelevant at this point in time, it seems to be in the far future. Spenders and savers in Argentina are in for a nightmare this month and next as the economy experiences a rare time of abnormality. When the dollar yield falls by the same percentage as the peso interest rate, it becomes irrelevant whether the saver loses more money investing in fixed-term deposits or greenbacks when the peso interest rate is barely over half of inflation. Pensions, which doubled in 2023 despite a tripling of prices, have taken an even worse hit than real wages, which have declined by over 20% since the beginning of the year. Recession is on the horizon for retail centers, manufacturing facilities, and construction firms due to stagnant public works projects and shrinking consumer markets.

There will be sacrifice on nearly every front (with symbolic gestures here and there, but no real indication that the caste will take the weight) during the time that Milei has predicted will be the most difficult as he resurrects Argentina. However, it is also necessary to distinguish between the nearly universal difficulties that may be considered collateral damage at this stage of the cycle and the more long-lasting damage. There are two distinct groups in the second group: retirees and small companies.

No matter how much of a contribution pensioners have made to the budget surplus that was achieved at the beginning of the year—more than a third of the cuts, nearly equal to the combined impact of the other three major austerity targets—energy and transport subsidies, public works, and transfers to the provinces—they will still face additional punishment. The irony is that Milei and his economy minister Luis Caputo didn’t come up with this astounding savings of nearly a trillion pesos; rather, it was the outcome of cynically maintaining Alberto Fernández’s very flawed updating system. Since a guaranteed pension provides a modest safety net that is far better than the uncertainties of informal employment, and since the young are the future, the libertarian movement among young people could become even more extreme if left to its own devices. It has been noted that over 60% of the youngest people live below the poverty line, while only 15% of the oldest do.

Shrinkage in sales might be a cyclical issue for small businesses, but the impending loss of subsidies might lead to electricity bills in the seven figures, which could put most of the unending rows of mom-and-pop stores along this city’s avenues out of business.

But get ready, because May is both a month and a verb, so the next two months are bound to be challenging.